Yellow-Naped Amazon Numbers Are Declining in Most Habitats

The yellow-naped amazon parrot, native to coastal regions from southern Mexico to northern Costa Rica, is currently hovering on the brink of extinction. This is due in part to habitat loss caused by agricultural development, as well as heavy poaching into the illegal pet trade throughout Central America. In the 1990s, almost 100% of known nests in southern Guatemala were poached. A 2016 survey of the species’ population yielded a count of only 1,682 birds in Costa Rica and Nicaragua combined, a sharp decline since the previous survey in 2005.

Efforts to Increase the Parrot Population in Paso del Istmo

One of the few remaining areas where the yellow-naped amazon (called lora de nuca amarilla in Spanish) can still be found is the Paso del Istmo (Passage of the Isthmus). It is a narrow bridge of land in Central America between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific coast, and it’s currently the only habitat in which the parrot population isn’t declining.

Instead, conservation programs led by organizations like Paso Pacífico, One Earth Conservation, and Loro Parque Fundación near Lake Nicaragua have helped to stabilize the local yellow-naped amazon population—and as of 2020, the numbers were even showing signs of increasing. In the same year, these efforts helped a record number of 39 fledglings graduate from the nest to independence in Nicaraguan forest lands.

Here are some of the strategies that have helped to accomplish this:

- Placing artificial nests near previous nesting sites in trees damaged by poachers

- Monitoring natural and artificial nests using camera traps

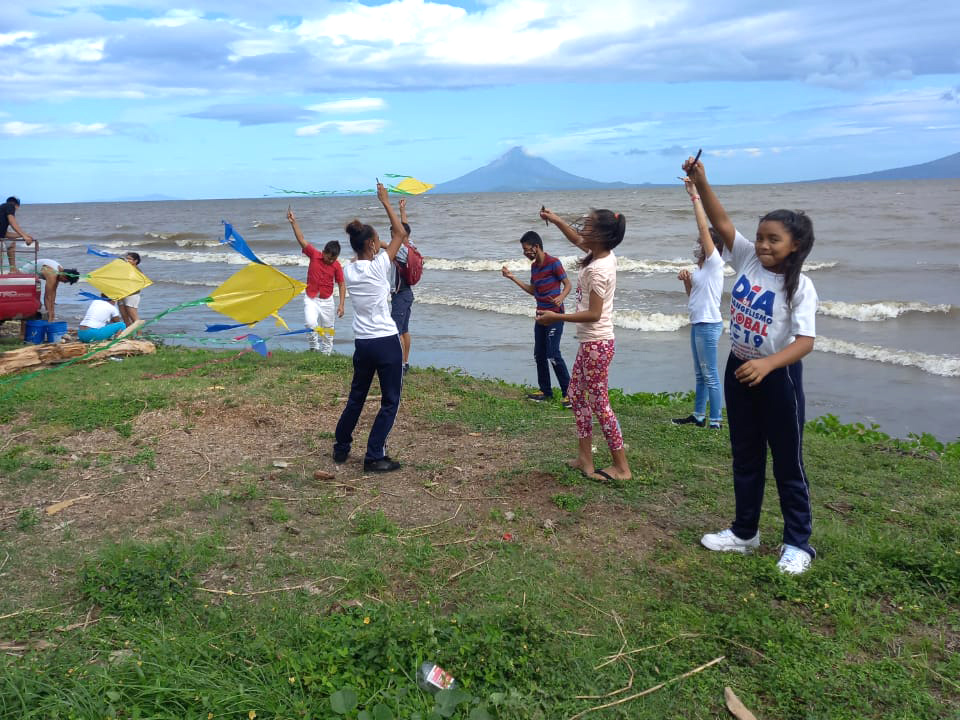

- Educating young people and adults about the plight of these amazon parrots

- Paying local families more money to help protect nests than they would earn as poachers

Continuing efforts to save even more yellow-naped amazon parrots include forming a national conservation plan in collaboration with El Salvador’s Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources.

Help Increase Yellow-Naped Amazon Parrot Populations with Paso Pacífico

An excellent way to help save endangered species like yellow-naped amazon parrots is to support conservation organizations. Paso Pacífico is accomplishing important steps in protecting these beautiful and intelligent birds. In fact, Paso Pacífico is heavily credited with conservation successes in the Paso del Istmo.

At Paso Pacífico, our mission is to create wildlife corridors that safeguard biodiversity while connecting people to their land and ocean. Our goal is to restore and conserve Mesoamerica’s Pacific Slope ecosystems. The threatened mangrove wetlands, dry tropical forests, and eastern Pacific coral reefs are among these ecosystems.

All conservation programs at Paso Pacífico benefit directly from your donations. These include education programs that teach children the principles of biology, ecology, and environmental citizenship. Contact us today!