From Red Orbit:

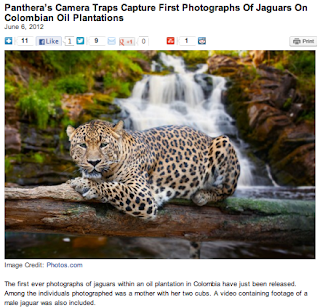

The first ever photographs of jaguars within an oil plantation in Colombia have just been released…

Panthera, the world’s leading wild cat conservation organization, focuses solely on the study and conservation of wild cats. The camera traps placed by Panthera in the Magdalena River valley were meant to gather information about the dangers of Colombia’s growing oil plantations on the jaguar populations. Panthera’s objective is to understand how the plantations affect the jaguar’s ability to move throughout its habitat, reproduce, and the effects on species that the jaguars prey on.

On beaches, poachers snatch up their eggs and babies for stewing; at sea, adults get snagged by fishermen’s long lines and nets. Now, climate change joins the list, threatening the survival of critically endangered leatherback sea turtles in the Pacific.

On beaches, poachers snatch up their eggs and babies for stewing; at sea, adults get snagged by fishermen’s long lines and nets. Now, climate change joins the list, threatening the survival of critically endangered leatherback sea turtles in the Pacific. We are among those working to alleviate the threats of fisheries and development, and protect Leatherback, Olive Ridley, Hawksbill, and Green sea turtles. We are pleased to share the many ways we are working to mitigate climate change and ensure the survival of sea turtles.

We are among those working to alleviate the threats of fisheries and development, and protect Leatherback, Olive Ridley, Hawksbill, and Green sea turtles. We are pleased to share the many ways we are working to mitigate climate change and ensure the survival of sea turtles. You can help!

You can help!