By Jason G. Goldman

Every year, millions of birds of prey migrate from summertime breeding grounds in North America to overwintering grounds in South America. One section of their pathway stretches nearly 2500 miles between central Texas and northwestern Colombia’s Chocó rainforests and is known as the Mesoamerican Land Corridor. More than five million raptors – the family of birds that includes vultures, hawks, eagles, and owls – can be seen making the journey each year. It’s the most important flyway for raptors in the Americas.

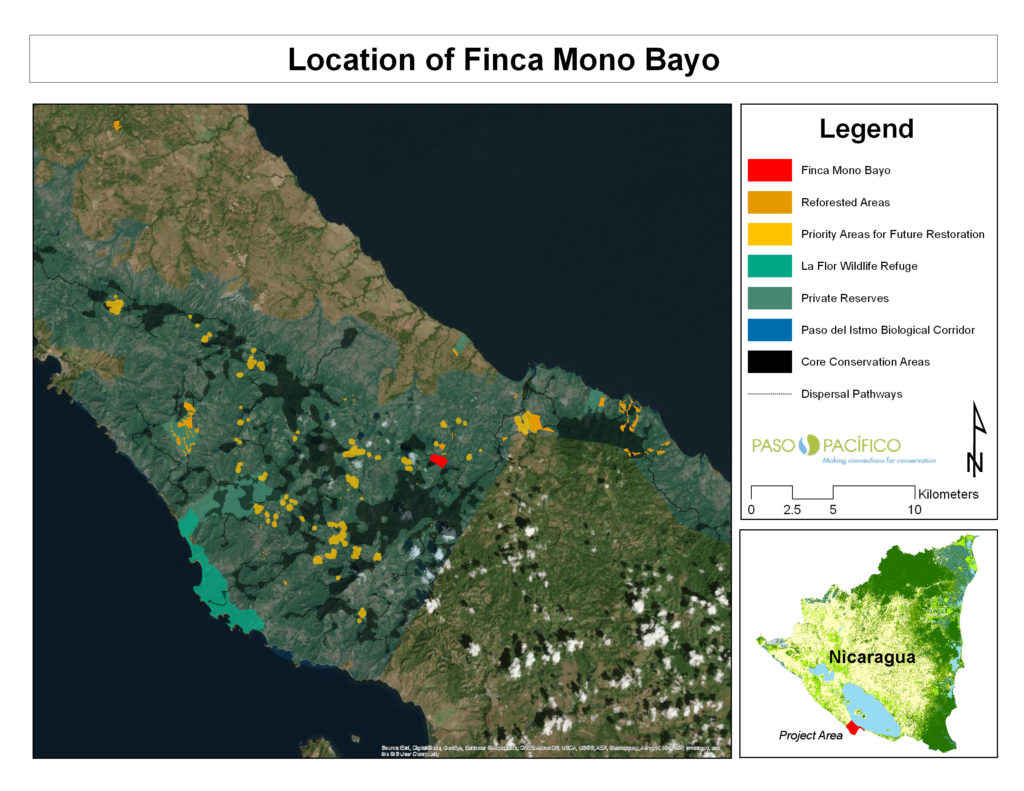

More than one million of them pass through a narrow stretch of southern Nicaragua, bounded on the west by Lago Cocibolca and on the east by Reserva Biológica Indio Maíz. That’s according to a survey conducted in 2019 on behalf of Paso Pacífico in San Miguelito. Over just twenty-three days of monitoring, biologists counted more than 1.2 million raptors passing overhead. Just over eight hundred thousand of them were turkey vultures. Also abundant were Swainson’s hawks and broad-winged hawks. In all, they documented sixteen different types of raptors.

The importance of this region for raptors has been known since at least the year 1555, when a Spanish colonialist named Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés wrote about the seasonal movements of large flocks of raptors through eastern Panama. Nearly five hundred years later, there’s still a lot left for avian biologists to learn – especially about the section of the flyway that passes through Nicaragua.

With strict coronavirus protocols in place, the Paso Pacífico team returned to San Miguelito this year to repeat the raptor count. The effort has been extended from one to two months. Halfway through the study, the team reported early results: they again counted more than 1.2 million raptors in the first month of monitoring. As before, the most common species were turkey vultures, Swainson’s hawks, and broad-winged hawks.

“Everybody knew that the raptors were passing through Nicaragua,” says Sarah Otterstrom, executive director of Paso Pacífico. “It’s not like they’re disappearing between where they’re counted in Belize and where they’re counted again in Costa Rica and Panama,” she explains. But nobody had ever bothered to identify exactly how they are using Nicaraguan airspace, or what habitats they rely on as stopover sites.

That’s why Paso Pacífico intends to construct a permanent raptor monitoring station in the area. After completion, it will join a network of more than a dozen similar sites along the Mesoamerican Land Corridor that, together, will paint a complete picture of raptor movements in the Americas.

The station will be named in honor of Luis Fernando Díaz Chávez, a Paso Pacífico bird technician who pioneered the first year of the raptor monitoring study at San Miguelito. He died in June after spending nearly a month in and out of the hospital with COVID-19.

Just thirty-one years old, Luis had been a regular contractor on Paso Pacífico’s bird projects for the last nine years. “He really loved raptors,” says Otterstrom. “He had written a draft of a Raptors of Nicaragua book, with his own photography, that we are trying to finish and publish for him.”

Luis came from a big family in Managua, where he shared a home with his parents, his grandparents, his brother, and many aunts, uncles, and cousins. Though his family did not have many financial resources, they helped him become first in his family to graduate college.

After his father died several years ago, Luis became a high school science teacher. The career move meant a more predictable salary than jumping from project to project as a bird technician for Paso Pacífico. “Luis would send most of his payments to his mother,” explains his colleague Oswaldo Saballos, who counted Luis as a friend and as a mentor. Anything left over would be spent on birding guides or other tools to fuel his passion.

Despite his full-time employment as a teacher, Luis still found time to lend his ornithological talents to Paso Pacífico when he could. Over the years, he taught more than five hundred children to observe birds. “He was one of the best birders in the country,” recalls Otterstrom, especially when it came to identifying birds based only on their songs and calls. “I think that his gentle, shy, quiet personality gave him this really supernatural ability to observe and perceive nature,” she says.

After the raptor monitoring station in Luis’s honor is completed, Otterstrom hopes it will attract birdwatchers and other tourists passionate about wildlife and nature. Local communities could therefore leverage the ecological value of the region for economic gain. “This area is where the Nicaraguan government wanted to run the canal. While that project is no longer a threat, it’s important for conservationists to put this space on the map in terms of its ecological value and importance,” she says. “We need to make sure we protect these migratory corridors for raptors and other wildlife.”

Panorama of the 2019 initial monitoring station located in Rivas, Nicaragua, photo by Vincent Romera.

Top photo: Turkey vultures (Cathartes aura) spotted during the 2019 raptor monitoring, photo by Vincent Romera

1. Share

1. Share 3. Invite.

3. Invite. 4. Thank!

4. Thank!